Following the end of World War Two, the US moved into an era of prosperity. Dad went to work each day. Mom stayed home and raised the kids. The kids went to school and in the afternoon they studied and played outside. There were new cars, yearly vacations, weekends away, perhaps some extra money to purchase things such as a lakeside house. A lifestyle that appeared picture perfect.

Yet viewed from the inside there were cracks in the facade. Underneath the smiles and waves, there was a growing deep psychological fear of atomic war. The US and Russia were engaged in a nuclear arms race, each country doing their best to have more armed missiles on hand, targeted at their enemy’s most populated cities, should the other side decide to fire their missiles.

Due to the fact that both sides were posturing and neither dared to actually engage the other, this period of time was referred to as a “Cold War”. Each country spending millions of dollars each year to build up their military, filled with soldiers, armaments and generals they dare not use. Instead, the Cold War was fought by virtually unknown men and women, often behind enemy lines. Spies and secret agents, gathering information about their enemy and communicating that information back to their home country. These agents took on many different roles, infiltrating their enemy’s scientific and power structures, either quickly, out of some perceived urgency, or over a great deal of time, as sleeper agents, embedded within their enemy’s country for years.

The Cold War was a war fought over the trade of information and political influence, at first focused on their enemy’s home countries. As time marched forward, though, the Cold War was fought worldwide as both the United States Of America and Russia expanded their economic influence into other countries, in South America, Asia and the many countries on the continent of Africa.

The public awareness of the Cold War as it was being fought was centered on the threat of Communism, with figures such as Senator McCarthy stoking the flames, in a somewhat unamerican, and perhaps even unconstitutional manner. The less overt manner by which the public heard of the battles fought during the Cold War were from the rise of spy and secret agent novels.

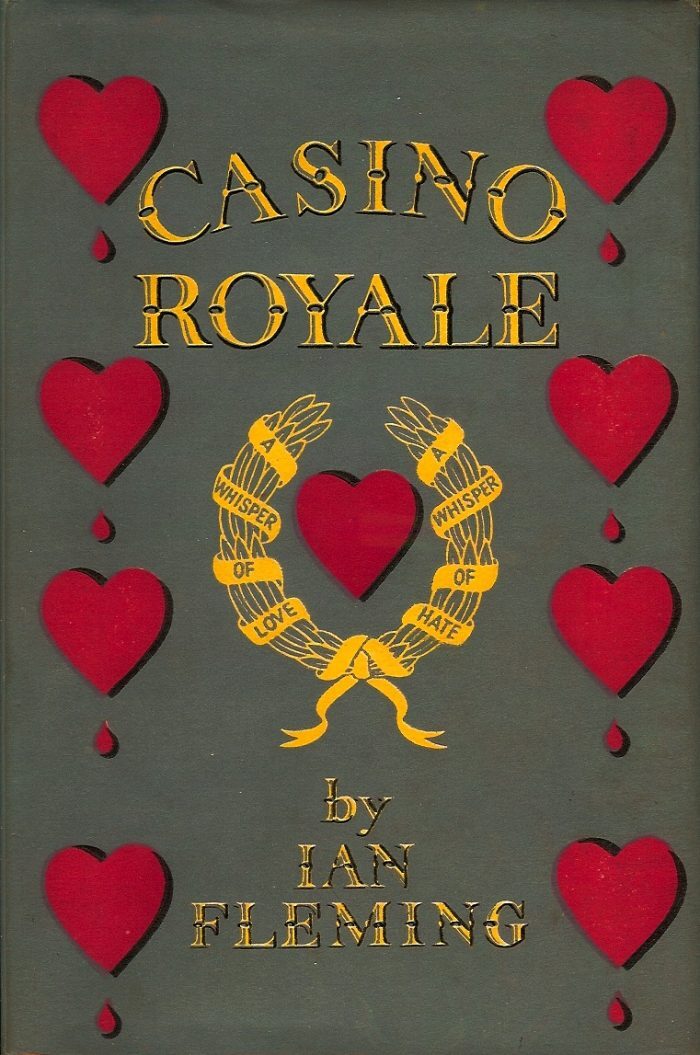

Ian Fleming published his first novel featuring his secret agent protagonist, James Bond, “Casino Royale,” in 1953. The novel was a great success and he wrote another eleven novels about the character, which were published annually until his death in 1964.

Fleming’s novels centered around the operations of British intelligence, the Secret Intelligence Service or MI6. In the books, James Bond is assigned to the Double O section and designated as “007”. This fictional government department granted its agents a license to kill. James Bond then was not a spy — a person gathering and extracting information — but a secret agent, a human instrument, whose task was to destroy the enemy, by any means necessary.

In 1960, Donald Hamilton published a paperback novel entitled “Death Of A Citizen,” featuring Matt Helm, a fictional character, who had been part of an agency that tracked down and assassinated Nazis during World War Two. Helm is drawn back into the agency through a series of events; over the course of 27 novels, he hunts down and kills enemy agents, in what is often referred to by the author as “counter assassination”. Matt Helm, like James Bond, is not a spy, but a secret agent. The fictional agency, for whom he works, is never given a name in the novels, but its task is clear: killing assassins who work for the opposition. The Matt Helm series was written in a matter-of-fact tone, with a certain amount of detachment to the violence in the stories. The novels sold well, the last of them was published in 1993.

The popularity of these secret agent novels did not go unnoticed by the movie industry and in 1962 “Dr. No”, the first film featuring James Bond, was released. This film was the launch of one of, if not the most successful, film franchise in the history of film. “Dr. No” was an instant success. It portrayed spies and secret agents in a manner that had not been seen before on the big screen. Prior to this film, spies had operated in secret, hiding in the shadows, skulking around and doing their best to remain anonymous, while in the James Bond film series, the character is portrayed as handsome, debonair and somewhat brash. Bond is seemingly equally adept at mixing with all strata of society, bedding women, and slaying his opponents.

To accompany this bold new portrayal of the secret agent in cinema, the movie studios enlisted composers to create a new type of music to appear as the soundtrack to their films, a genre I have always referred to as “Spy jazz”.

The soundtrack for “Dr. No” was rather typical for the era, with incidental songs and musical cues for the action that appeared in the film. The popularity of the film franchise itself would change all aspects of the later movies, including the soundtracks for future James Bond films. But this first soundtrack does have what has become one of the most iconic and identifying piece of music in all of movie history: The James Bond Theme. Contrary to popular opinion, the theme was composed by Monty Norman, not John Barry, who would compose the music for the subsequent James Bond films. The James Bond theme is a genius piece of music, a guitar-lead orchestra that explodes in the center with horns and strings, only to return to the stinging guitar signature sound before fading out. This piece, and variations of this piece, would appear in each of the subsequent James Bond films.

The popularity of the James Bond novels also had an impact on the television industry. In 1960, The British Television company ITC produced the show “Danger Man,” starring Patrick McGoohan as John Drake. The first series consisted of half hour episodes filmed in black and white. Many exotic locations were used during the series: Europe, Africa and the Far East. Subsequently, the soundtrack reflected the exotic locations, incorporating a variety of instruments, such as the prominent harpsichord on the theme song composed by Edwin Astley.

In 1964, the show was reinstated and sold to the American market under the name “Secret Agent ”. This new series appeared as hour long episodes which allowed for greater plot and character development. Lead actor Patrick McGoohan’s influence over his character, John Drake, remained strong. Drake operated with a high moral standard, solving situations with his wits rather than firearms and treating female characters with respect. The show made one obvious concession to the American market, replacing the original theme song by Edwin Astley with a song by Johnny Rivers, entitled “Secret Agent Man”.

American television industries realized quickly that interest in spy and secret agent dramas was at an all time high and the various studios produced such shows as the 1964 hit, “The Man From U.N.C.L.E.” Despite the Cold War era in which it was produced, this show featured an American and a Russian agent working together to thwart an evil international organization. This show was a bit tongue in cheek, taking itself not too seriously. The music for the program was arranged and conducted by Hugo Montenegro and incorporated many lounge and exotica elements, to accompany the many international locations for the show.

In 1965, NBC launched the show, “I Spy,” which was unique for a couple of reasons. One was the fact that it was the first American television drama to feature an African American actor in a lead role, and another that the show was actually shot in international locations, such as: Hong Kong, Athens, Rome, Florence, Madrid, San Francisco, Las Vegas, Venice, Spain & Morocco. The show, “Man From U.N.C.L.E.,” was shot on the backlot of Desilu studios, which lent a feeling of standard backdrops to the show that “I Spy” overcame with their authentic locations. The music for the show was composed by Earle Hagen, and the theme is a masterpiece of driving bass with punctuating string and percussion accents.

Also launched in 1965 was the television show “The Wild, Wild West” by CBS. This show was a nice mix of the secret agent and science fiction genres, and was decidedly tongue in cheek, following the adventures of two agents for the American government, in the years following the Civil War, riding across the American West in a private train and solving crimes committed by such villains as Dr. Lovelace. The show was filled to the brim with gadgets and evil machinery, so much so that in retrospect it might now be viewed as a steampunk classic. The theme song was a jaunty piece well-reflecting the western theme of the show, which played over a series of animated graphics.

The following year, in 1966, CBS launched a show that was very popular and that in later years inspired a very successful film franchise, “Mission: Impossible”. The series followed a rotating group of agents operating for an independent government agency, who, with subterfuge, disguise and sleight of hand, go up against evil organizations, dictators and crime lords. The music for the show was composed by Lalo Schifrin; the theme song may be the most recognized in television history.

At the height of spy and secret agent public interest, Columbia pictures released “The Silencers,” the first of four Matt Helm films starring Dean Martin. Unlike the James Bond films, which were serious in tone with an undercurrent of humor, the Matt Helm films were intended to be a spoof of the genre. In many ways. this approach represented the direct opposite of the tone of the novels, from which the character was drawn. Despite the comedic nature of the film, the score by Elmer Bernstein was right in line with the upbeat spy jazz of the era.

During the latter half of the Sixties, the obvious success of James Bond and spy / secret agent television programs sent every Hollywood producer scrambling to make a film or show to fit in with the genre, including films such as: “Our Man Flint”, “Modesty Blaise”, “Danger Route.” Many of these may not be worth the film used to make them, but nearly all of the them had interesting soundtracks, or at least a song or two that stood out — making them ideal for crate diggers searching for interesting instrumental pieces to spin.

Soundtrack records are more often than not a treasure waiting to be uncovered, even for a single song alone. But the well played, exotic mix of instruments and themes that comprise these “Spy Jazz” records ensure that these soundtracks are filled with music that continues to garner interest, even after the films have ended and the television screens have faded to black.

Noah Fence hosts It’s a Nice World To Visit – Punk, Post-Punk, Garage Rock, Psych…A mix of new tracks and old favorites. On Freeform Portland Radio.