It’s never been quite enough to correct the mainstream record, but lots of ink has been spilled over the years on how punk rock’s truest, bluest bug juice first bubbled to the surface not in New York or London, but in Cleveland, Ohio, a full couple years before anyone rolled over and told Joey Ramone the news. Cleveland’s under-nurtured early ’70s freak scene was, in this writer’s estimate, punk’s form and spirit at its most undiluted, and almost definitely its furthest off the wall.

Unlike most of the glam-weaned punks of New York and London, the members of legendary Cleveland proto-punk bands like Rocket From The Tombs, the electric eels, and Mirrors were a bunch of legit freaks, way too gawky and weird to even dream of being Bowie/Bolan pretty. Instead of debauched glamour, these bands would drown all comers in waves of exaggerated, bleakly funny negativity, blasting out no-fi chunks of dada garage mayhem to virtually nobody. Even punk early-adapter/champion Lester Bangs, only a couple hours north in Detroit at the time, couldn’t be bothered to give these nutjobs the time of day.

They were snot-drenched reprobates all, as poisoned by the Stooges/Velvets toxin as anyone, but the Cleveland punks also had a shared something — by dint of their age bracket and concomitant status as the first fully TV-damaged generation — to which none of the coastal correlatives could lay claim, and which was perhaps the biggest influence of all. Cleveland had Ghoulardi.

Let’s start with the bare trivia first: for most of his professional career, Ghoulardi was known by his given name of Ernie Anderson. Outside of the greater Cleveland area, he’s far more remembered as the voice of ABC in the 1970s-90s. His voice is perhaps most recognizable to Xers and millennials from its omnipresence on America’s Funniest Home Videos; older folks hear Anderson’s voice and immediately think of The Love Boat. Before moving to Los Angeles and breaking into his career-defining gig, though, Anderson was a local radio and TV talent in Cleveland. Though he’d been a journeyman announcer and radio personality along the east coast for years, it was Cleveland where Anderson first really made a name for himself.

After some time building his announcing portfolio and struggling to find a consistent place at the Cleveland TV station KJW, Anderson was asked by the station brass to jump into a late night “horror host” role. In the 1950s-60s, horror hosts were a common sight on local TV, a way of adding local context to Universal’s syndicated “Shock Theater” package (a collection of old monster movies which were sold to local stations for late night programming). Usually, these hosts would don a cape or some monster makeup, assume a corny Dracula/Vincent Price accent, and try to spook the kids a little.

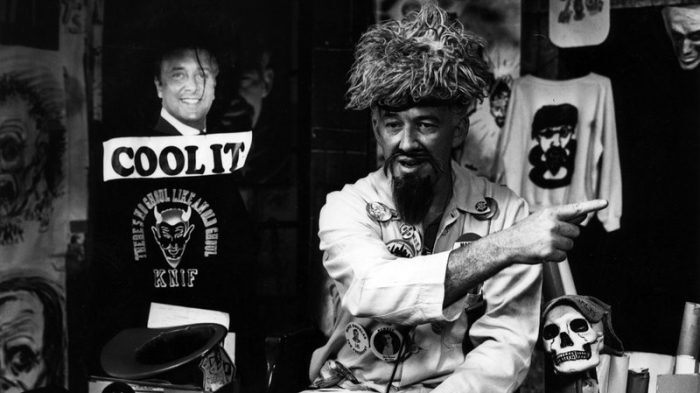

This, though, would not be Anderson’s style. As Ghoulardi, Anderson slapped on a fake Beatnik goatee and a messy, ill-appointed fright wig, and draped himself in a lab coat festooned with slogan buttons (initially, this disguise was as much to save face as to attract attention, as Anderson was concerned that such an undignified gig might compromise his announcing career). To disguise his distinctive voice, he would talk in a vaguely Eastern European brogue, albeit one peppered with myriad hipster phrases of the day and a series of signature slogans: “STAY SICK!”, “THE WHOLE WORLD’S A PURPLE KNIF”, “TURN BLUE”, “HEY, GROUP!”.

Through his 1963-66 run, Ghoulardi was an outright phenomenon in the greater Cleveland area, his face emblazoned on everything from t-shirts to shot glasses. His catchphrases and slogans became ubiquitous local slang, and Anderson would be swarmed in public places as if he were Elvis.

What does that have to with punk rock, though? Really, it’s mostly a matter of attitude. As Ghoulardi, Anderson could get away with slagging off whoever he felt deserved it. He mocked the films he was tasked with showing, the people of the nearby town of Parma, his crew, his bosses, and most especially any local media personality who came off as a pious stuffed shirt. Anderson also had a habit of setting off fireworks in the studio (one of his beloved catchphrases, “cool it with the boom booms!”, is inspired by this practice, and most especially his tendency to go too far with it) and riding his motorcycle through the TV station offices. In short, Ghoulardi was pure, raving id, always in search of cheap thrills regardless of the concerns of “The Man”. Sound familiar?

Anderson’s madcap, confrontational humor would bend the brains of a whole generation of Clevelanders, and many of that generation would go on to form weird rock bands in the 1970s. These bands — the aforementioned electric eels, Rocket From The Tombs, Mirrors, and later Pere Ubu, The Dead Boys, Tin Huey, and several others — were heavily indebted to Ghoulardi’s overarching aesthetic, not to mention the noisy ’50s rock/R&B sleaze favored by Ghoulardi’s right hand man and de facto music director, “Big” Chuck Schodowski.

Craig Bell, who would play bass with Mirrors in the mid-70s, remembers the inspiration well. “I was eleven that year (1963, when Ghoulardi debuted), and my parents would let my brother and I stay up late to watch Shock Theater, which presented cheesy monster and sci-fi movies,” Bell says via email. “The host was everything an eleven-year-old kid wanted to be: he dressed weird, spoke weirder, and blew stuff up!”

Michael Weldon, Bell’s Mirrors bandmate who also did time in top-notch Cleveland freak crews Styrenes and X_X, gives Ghoulardi a huge amount of credit in inspiring his work, especially his long run as founder/editor of the legendary oddball movie magazine Psychotronic Video. His account backs up Bell’s: “All the right ingredients: right guy with the right (bad) attitude at the right time, showing many of the best movies (most from Allied Artists and AIP) and serials and shorts, plus the coolest possible music and hilarious audio and visual gags and interruptions. His influence lived on in other cities, too, thanks to hosts who copied him, including the syndicated [and sadly, recently deceased] Ghoul (The Stooges’ Ron Asheton was a fan) and, less directly, the original Svengoolie in Chicago.”

Weldon, for his part, has been more than happy to shout Ghoulardi’s name to the heavens over the years, even going so far as to write a tribute to him for Fangoria in 1982, along with multiple articles for his own magazine. When asked how Ghoulardi still influences or guides his creative pursuits, Weldon simply replies “too many ways to list. He’s up there with MAD magazine”.

Weldon’s not alone in acknowledging a debt to Ghoulardi. In 2005, Pere Ubu and Rocket From The Tombs frontman David Thomas wrote a great essay, ‘Ghoulardi: Lessons in Mayhem‘, extolling the virtues of Anderson’s character and its essential impact on his generation. The Cramps, whose late frontman Lux Interior was an ex-Ohioan, even went so far as to name the band’s 1990 LP Stay Sick! as a tribute to Anderson. John Morton, of the electric eels and X_X, was quoted by NPR a couple years back as saying “(Ghoulardi) was really an iconoclast in the true sense of the word, you know, in breaking established things. It was great for kids, this kind of defiance.”

Of course, not everyone who was a kid in 1960s Cleveland grew up to form a rock band. One Cleveland kid, Drew Carey, was spotted wearing a Ghoulardi t-shirt on his eponymous 1990s sitcom. Director Jim Jarmusch, a native of suburban Cuyahoga Falls, was also a big fan: “he’d come on with this weird circle of light around him, and then they’d reverse polarity to create these wild flashes of color,” Jarmusch told the Cleveland Plain Dealer’s John Petkovic (himself a part of the Ohio rock lineage, having done time as a member of Death Of Samantha, Cobra Verde, and Guided By Voices) in 2013. “Then he’d insert himself in the movies and warn the viewer, ‘look out, kids, the crabs are coming.’ It blew my mind.” The recurring use of Screamin’ Jay Hawkins’ demented R&B bellow “I Put A Spell On You” in Jarmusch’s 1984 breakout film Stranger than Paradise was directly inspired by Big Chuck’s use of the song on Ghoulardi’s show.

Ghoulardi’s biggest mark on popular culture, though, might have been less direct. After Anderson moved to California, he fathered a son, Paul Thomas Anderson, and instilled in him a strange, irreverent sense of humor. The younger Anderson would later go on to apply that humor in his lauded films; one famously tense, firecracker-laden scene in Boogie Nights is an acknowledged tribute to the elder Anderson’s obsession with “boom booms”. If there were ever any doubt where the kid gets it from, PTA lays it to rest with the name of his production company: “Ghoulardi Pictures”.

Still, Cleveland’s proto-punk scene was where Ghoulardi’s influence was first seen clear as day, and debatably where it was the most essential nourishment. Rather than try to sum it up neatly myself, as an outsider looking in, I’ll leave it to David Thomas to do the deed. He puts it as such in that aforementioned lecture:

Why was it such a specific and limited generational window? What was the source of such rage, such disaffection from not only the mainstream culture but also from the so-called counterculture – in fact, from any subculture you’d care to mention? What could produce such a contradiction as this set of radical innovators who embraced consumerist media with such enthusiasm?

The answer for many of us is simple. We were the Ghoulardi Kids.

If you want to learn more about Ghoulardi, a nice documentary was made about his reign some years back, and it’s available on Youtube. For even more info, check out the very informative book by Tom Feran and R.D. Heldenfels, Ghoulardi: Inside Cleveland TV’s Wildest Ride.